King of the River

Last summer, while wandering through Hyde Park, I stumbled upon a surreal scene – a masked figure playing accordion under the trees, slowly gathering a crowd like the pied piper. My casual walk at Nichols Park turned into an encounter with an immersive, public performance that stayed in my memory for months to follow.

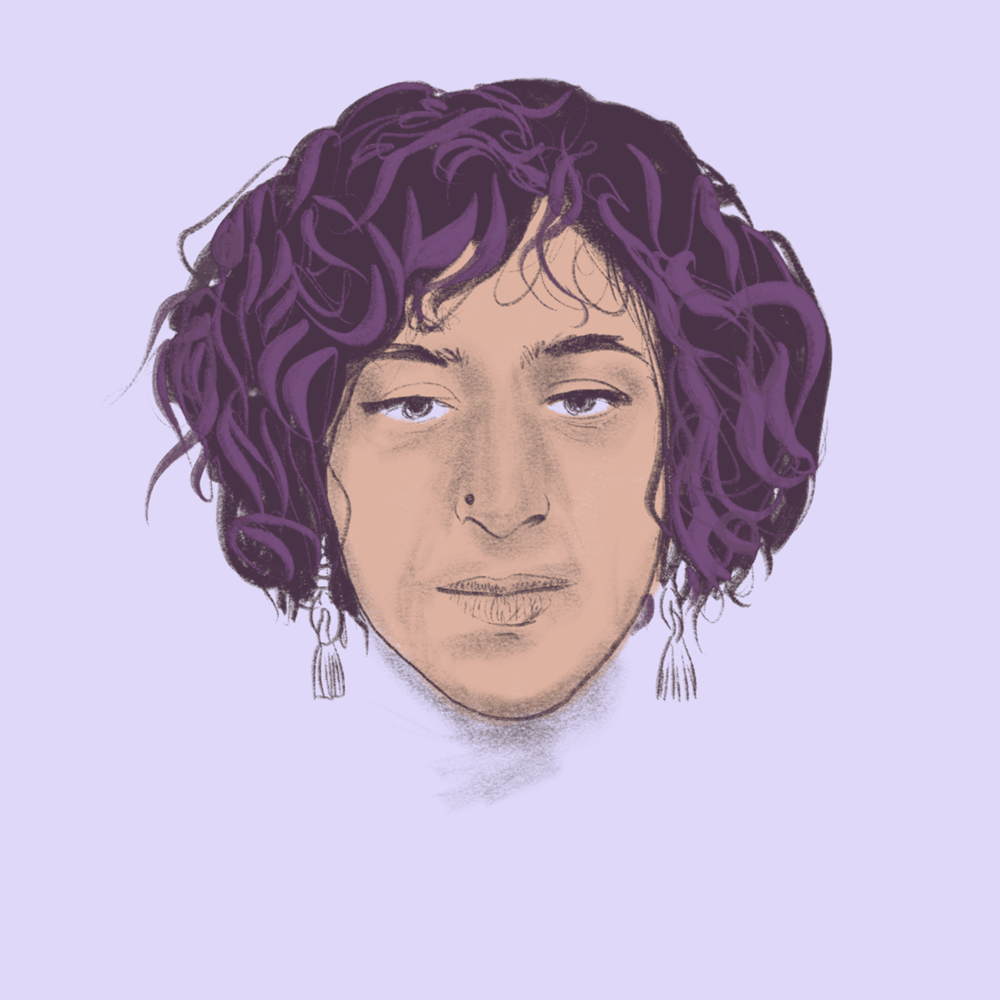

This May, I saw the artist again. This time, by the water. There were boats, masks, and music, but now there were hundreds of people. I spoke with the artist, who calls himself “King of the River,” about making work in public spaces, contextualizing sound, and making a living as an artist.

Khytul: What was it like returning to the Secret River Shows this year?

Lawrence: This was the most people we’ve ever had! Maybe 400 or so. It’s fun, and I think part of the artistic idea is: how do you connect with people through music in this day and age? Everyone receives things within a context. I want to create the context in which a song can be received, where the whole day builds toward the moment of the song.

K: So for you, it’s about crafting the setting, not just the sound?

L: Exactly. You could be at a bar and hear a song, and it might be beautiful, but you don’t know it’s important. I think the experience of music has changed, people aren’t hatched into music anymore the way they were. You hear 80s rock guys talk about seeing an artist at a specific show, at a specific moment that was shared with a group of people. I’m trying to bring that back. A memory that plants the seed of a song into your life’s story.

K: I think it really succeeded at that. For me, that memory of Hyde Park will stay with me, especially since I may be leaving the U.S. soon.

I’m from elsewhere, and this felt like one of those rare experiences I came here to find.

L: That’s really meaningful to hear. For me, the spirit of the work is about freedom. I’ve never gotten a permit for a show. I think there’s faith involved; faith that humans want these kinds of things to happen. There are rules for a reason, sure. But we shouldn’t let the rules guide the moment of creation. We can figure it out later.

K: You call yourself “King of the River.” Where did that come from?

L: It was inspired by Don Quixote. He believes himself to be a knight errant — and he acts as such, until other people then believe that he is. Eventually, in the second book, everyone’s read his book. I feel like I’m entering my second book now.

At first, it was a funny, audacious claim. But then, the Woman of the River bestowed a sword on me. I accepted it. And since then I’ve been king.

K: I’m asking these as an artist too — how do you make a living doing this?

L: That’s a great question. Right now, I’m supporting myself on river shows. I do music in a lot of capacities: I play piano for improv comedy, I play the organ for magicians. So I'm an accompanist, which is a gig that can pay.

K: What other jobs did you have to do before you could sustain yourself with music?

L: Before this, I worked a bunch of service jobs — bartender, server. A lot of artists I know in Chicago work service jobs, because they allow you the flexibility to pursue your practice.

But once the pandemic hit, I told myself I’d try to sustain myself through art, and it’s a challenge because in America there’s not a monetary value to art. Like in France, they actually support the artists, in many countries there's funding that can connect to artists.

I’m also learning the grant system. But even that is more sparse in the US.

K: You’ve performed in so many different kinds of settings. What kind of audiences do you imagine when you perform?

L: Whoever is in front of me. The piece you saw at Hyde Park, 'E# Sonic Sight', was a crazy moment. It was the first time I worked with this theatre director from China, Sherry Wang, and we just really creatively jived. She was a visiting professor at University of Chicago. Music like this is inspired by the space. Like how do we use this park to the fullness of what it is. Each space asks for something different.

David Byrne talks about this in How Music Works: certain music is written for certain rooms. You don’t play chamber music in a DIY punk basement… but I kind of want to challenge that. Why not have a chamber choir in a DIY space?

There’s music that’s elevated to this “high” cultural status — but it’s all music. Punk DIY is the new folk. I call my genre “sad cowboy” because it creates an image that you can then associate with the music.

K: I wanted to ask about your eyeball mask. What’s the story?

L: I found it at the Wizard’s Chest in Denver. Costume and board game shop. I saw it and thought, “that’s cool,” so I bought it.

Later, I went hiking with some friends and brought a point-and-shoot camera. I had my friend photograph me wearing the mask in different spots in the woods. When I got the photos developed, I thought, “Whoa… this is a character.”

So, now I start each show with the mask, playing the accordion. It’s part of the invitation. I walk down the street with it, and it calls people in.

K: That’s what I saw last year, this invitation to play.

L: Yes, gathering the kids, leading them up the hill, making them ring a bell under the sycamore tree.

That’s the thing, I’ve learned that people are down to play games. You just have to create the way of inviting them in.

And once they’re in the game, they’re part of the whole thing.

%20-%20H.png)